Yesterday, I completed facilitating a leadership offsite. At the end of the day, as we sat around the firepit overlooking Maine’s Atlantic Ocean, one of the team members suggested we share a fun fact no one else knew. One of our themes of this offsite was to learn how to balance collaboration and taking personal responsibility, as they are flipsides to the same coin. I shared the following story.

I was part of a group that sang in Carnegie Hall. To a full house. And received a standing ovation.

But it started as an utter, undeniable disaster.

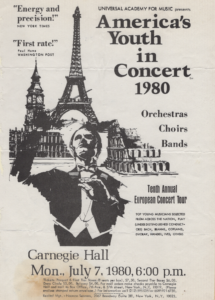

I sang baritone in a Concert Choir with America’s Youth in Concert, a group made up of 100 of the best high school singers from around the country. It was a wonderful growth experience that started out as sheer terror.

Me at Carnegie Hall, 1980. How the heck did I get here?!

In 1980, I was 17. My high school choral director nominated me, and I was invited to audition for America’s Youth in Concert – a group of 100 of the best singers across the US who would spend the summer touring Europe and playing concerts in venues like Notre Dame. To my amazement, I was selected to participate. Upon acceptance, they sent me the music: 16 choral pieces, some classical, some modern, some in German, and all with magical musical complexities. I spent the next 6 weeks at my piano practicing my baritone lines. This was challenging work, and it was hard to practice alone. I consoled myself not to worry. I was just one of 100 voices, after all. I didn’t have to be perfect. The sheer size of the group would hide my musical imperfections.

Our first concert was at Carnegie Hall. The weekend before the concert, a gaggle of 100 excitedly nervous young adults all arrived at Rider University in New Jersey. This would be our base camp. We spent the next 48 hours eating, drinking, and sleeping all things music. Rehearsals were intense. We sang every waking hour.

As the bus pulled up to the entrance of Carnegie Hall, my heart skipped a beat. My young mind was in awe of the building and our shiny new concert poster hanging in the front window. That was us!

Prof. Thomas Brooks, our choral conductor escorted us to the back entrance – the one that performers used. I thought: Tchaikovsky, Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Frank Sinatra any many other stars of musical genres had walked these same steps. The small, slightly crooked door opened to dimly lit tiny hallway that serpentined around corners. Eventually, we walked up a narrow set of stairs and found ourselves backstage. I stood on the stage and looked at the tiered balconies and wondered how the heck I got here.

Our concert that evening was sold out. Family, friends, and supporters of America’s Youth in Concert filled all 3,671 seats. I peeked through the curtain at the packed house and gulped. Walking onto the stage to take our positions on the tiered risers went in slow motion. Again, I reminded myself that I was only one voice of 100.

Brooks walked out on stage, took a bow, and turned to face us. He took out his shiny pitch pipe and gave us the starting note. He raised his arms and began his gentle rhythmic motion. And we began to sing.

It was awful. We were off key.

My god, we sounded like screeching metal.

America’s Youth in Concert: Us practicing at Carnegie Hall

Somehow, our 100 voices just did not map to anything we had practiced. He tried to bring us back, looking at each section – soprano, alto, tenor, bass, to nudge us back on key. But it just wasn’t working.

After 10 seconds (an eternity), his hands stopped in mid-air. Pinching the index finger and his thumb of his right hand, he pulled his hand across his chest from left to right, telling us to stop singing.

The tension on stage was palpable. The audience was deathly silent. I wanted to look at my colleagues, but I could not move. My eyes (all eyes) remained glued on to Brooks.

We had messed up beyond belief. I had messed up. Was this because I expected the group to carry me? Is this how everyone else was thinking? What if everyone else was thinking that the group would carry them, too?

But Brooks kept his composure. He didn’t get mad. He smiled. He turned to the audience and gently told them, “We are going to start again.” Now facing us, he panned the singers from left to right, miming, “it’s alright”, “you can do this.” Then, he instructed us to breathe with him. In slowly. Out slowly.

I knew I had to be better. I had to find a way through my insecurities and commit. I would not let the group carry me. I had to own my presence.

Again, he pulled out his pitch pipe and blew the reference note from which we would build our intricate harmonies. He smiled again. It was infectious. I smiled back. And through his gaze I found my confidence. He raised his hands again, brought them down, and we began to sing.

Our first chord resounded . . . and stuck! It was clear and clean.

And with that powerful entry, we knew – we all instinctively, collectively knew — we would succeed. In this historic, majestic Carnegie Hall, our voices echoed.

For the next several minutes our collective voices wove a tapestry of colors, high and low, soft and loud. And finally, with his hands held high, the waving motion of his baton signaled the final chord. We held it. . . and let it go. Like seeds off a dandelion caught in a gentle summer breeze, the notes of our music hung in the air and slowly faded.

Silence followed.

And then the crowd erupted. We could not believe it: They were on their feet! Not just because we sang the song well, but because we had crashed and had the courage to try again. And in our next attempt, we had nailed it. None of our rehearsals had produced music that was as good as what we had just performed.

Looking back, it is easy to understand that our practices were all about collaboration and learning how to sing together. But our collective failure inspired all of us to find the strength to take personal responsibility not just for us as individuals, but us as a group. This is the same lesson leadership teams face every day. Collaboration is a strength; it’s the key to teamwork and being a part of something bigger than any individual. However, collaboration will never take the place of personal responsibility. Because one voice, and every voice, in a group of any size, can make all the difference.

With a specialty in Customer Advisory Boards (CABs), Partner Advisory Boards (PABs), and annual planning offsites, Mike Gospe is a professional facilitator with a long history of leadership experience. He’s helped some of today’s most innovative companies deliver world-class programs in the US, Canada, Europe, and Asia Pacific. He leads KickStart Alliance’s CAB practice. He also has a very small, but not insignificant, footnote in the lessons learned at Carnegie Hall.